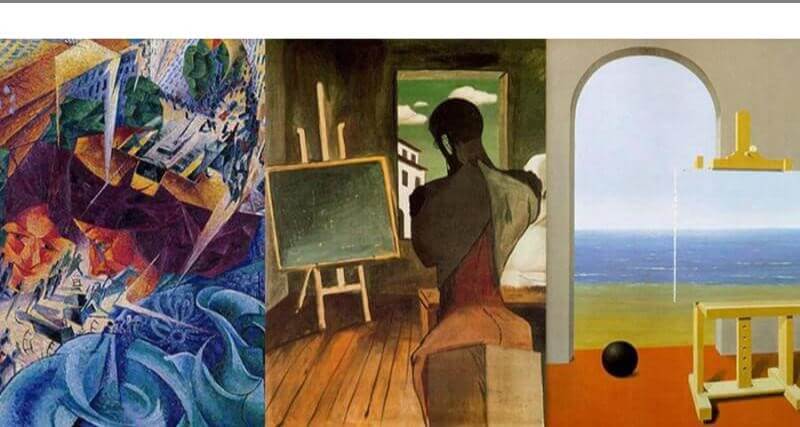

FUTURISTIC WINDOWS

In this painting, the futurist painter Umberto Boccioni portrays a woman from behind, leaning on the railing of a balcony. The view that opens from this position shows a dense series of buildings, a road on the left and construction sites in the central part of the painting.

The painting was exhibited at the first Futurist exhibition in Paris in 1912.

In the same year, Boccioni wrote the Technical Manifesto of Futurist Sculpture, but, more than the theoretical activity, the results achieved with his work immediately appear extraordinary. With sculpture, Boccioni created one of the most famous sculptures of this century. He investigates the plastic deformation of a human body in movement to then arrive at an aerodynamic shape where the body, although stylized, manages to convey a great sensation of strength and power. The statue becomes the very symbol of the man of the future, as the futurists imagined him: half man and half machine, launched into a race to travel the world with strength and speed. *1

The painters who presented their works (Boccioni, Carrà, Russolo, Balla and Severini) wrote a Preface on this occasion in which they reiterated the concepts already expressed in the previous manifestos of the Futurist movement and defined their work as “painting of states of mind”. . The state of mind is therefore in this work as in others the fulcrum of the conception of Boccioni’s painting.

Boccioni discovered that “true reality is sensation”, the only thing he can be certain of and the only experience of the external world he can have.

Boccioni himself describes his work in this way: “The dominant sensation is the one you can have by opening a window: all of life, the noises of the street, burst in at the same time as the movement and reality of the objects outside. The painter must not limit himself to what he sees in the window frame, as a simple photographer would do, but he reproduces what he can see outside, in every direction, from the balcony.” And again: “By painting a person on the balcony seen from inside we do not limit the scene to what the window painting allows us to see; but we strive to give the complex of plastic sensations experienced by the painter who stands on the balcony: sunny swarm of the street, double row of houses extending to the right and left, flowered balconies, etc. Which means simultaneity of the environment, and therefore dislocation and dismemberment of objects, scattering and fusion of details, freed from common logic and independent of each other”.

As in the other work from 1911, Simultaneous Visions, in the visual space of this painting we can observe in synthesis everything that surrounds the observer who leans out onto the street.

Looking out from the balcony, the woman not only watches, but is completely immersed and actively participates in the swirling human activity in the square below. The objects interpenetrate, overlap, intersect: the verticals become oblique as if to describe a body in movement: everything is frenetic and feverish. The buildings under construction seem to move and move towards the upper part of the painting, while pawing red horses, thrown from the road, burst out on this side of the balcony through the railing from which the woman looks out (in Boccioni not the car, but the horse , embodiment of nature’s energy, is the symbol of universal dynamism); everything moves in a whirlwind and seems to want to enter the house. Movement, vitality, frenzy: these are the sensations emanating from the painting. The theme we want to bring to life is the dynamism of the city rendered through an interpenetration of lights, sounds and movements that captures the infinite relationships between objects.

It is an exaltation of movement understood as simultaneity; the shattered and broken image is recomposed into a luminous vortex and an ascending whirlwind, lit by primary colors and drawn by lines of force.

Even those who observe the painting are catapulted into the same sensation of total immersion in the living forces of the city. Moreover, in the second version of the Manifesto of Futurist Painters of 1909, to which Marinetti himself contributed, in addition to the detachment from traditional realist painting and the desire for a new art that reflects the rhythm of progress and the conquest of the future, states: “The construction of paintings is stupidly traditional. Painters have always shown us things and people placed in front of us. We will place the viewer at the center of the painting.” For this reason the painting must be a battlefield between conflicting lines of force, which must envelop the spectator and drag him into the fray. Thus the futurist invention takes shape precisely by identifying the artistic object in the enjoyment of the public.

This framework adopts the programmatic indications outlined in the manifesto of the Futurist Painters and which can essentially be summarized as follows:

- the futurist artist is called to free himself from the tradition of the past and to seek the subjects of his inspiration in modern life, exalting everything that represents progress and innovation and therefore projects himself into the future (futurism as opposed to traditionalism);

- the futurist artist must celebrate movement, speed, dynamism and everything that represents strength and energy.

Beyond any ideology and any historical-political evaluation of the movement, Futurism is the most important avant-garde movement of the beginning of the century. It is based on the rejection of all traditional artistic forms; seeks a language suited to the new civilization of machines and based on the vitalism of the modern era. Futurism involves all artistic forms, giving rise to true masterpieces in the field of plastic and visual arts. At the basis of futurism was the intuition that the culture of the twentieth century could not fail to take into account the powerful processes of socio-economic transformation underway: rapid industrialization, the new structure and new function of cities, the triumph of speed, protagonist of the means of communication (such as the radio) and of the means of transport (the car, the airplane and in general those driven by the internal combustion engine), finally the same destructive violence of the new weapons. The futurists found the old conception of culture as a rational reflection and understanding of reality to be inadequate; thus they contrasted it with the idea of a culture centered on the need to act and on an artistic project capable of representing dynamism.*2 It undoubtedly concerns the Italian experience in its historical turning point from pre-industrial civilization to industrial civilisation, and manages to bring forward a effort of creativity and adaptation of languages to lived reality that no other intellectual deployment had been able to achieve.

Sources: