Renzo Piano and the architecture-nature combination

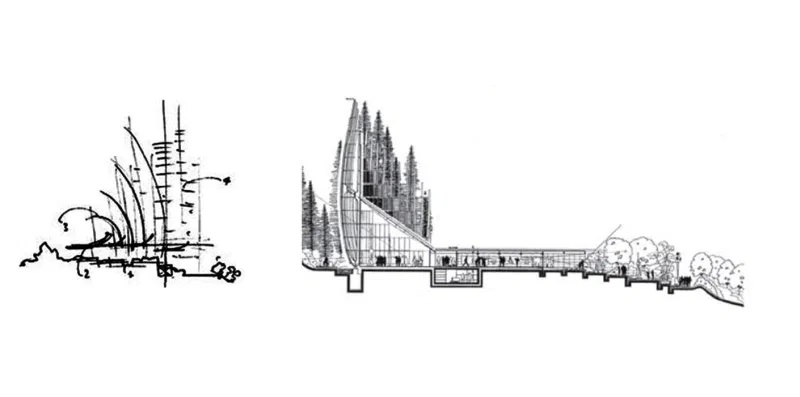

The Italian Archistar builds the Jean-Marie Tjibaou cultural center in iroko wood, technology and tradition in a close symbiotic relationship.

Having seen the work today, it is not difficult to imagine why the famous Italian architect Renzo Piano won, in the early 1990s, the national competition for the construction of a cultural center aimed at preserving the indigenous Kanaki culture, wanted by the then president Frenchman François Mitterrand, following the assassination of the independence leader Jean-Marie Tjibaou, which occurred on 4 May 1989.

Between 1995 and 1998, the Jean-Marie Tjibaou Cultural Center was born in Numea, New Caledonia, a French colony since 1864, a symbol and faithful guardian of local history and tradition, both for its purpose and for its architectural structure . The construction site, chosen together with the Kanaki community, is a paradisiacal island lapped to the East by the Pacific Ocean and to the West by the Coral Sea, where the overwhelming beauty of nature rightly reigns supreme.

What really wasn’t easy to imagine is the exciting ease with which an architectural complex of 10 units (the tallest measuring 28 metres), which extends over an area of approximately 8 hectares, could merge and mingle with nature and the adjacent landscape. What Piano managed to demonstrate with this grandiose work is precisely the symbiotic osmosis that can arise between architecture and the surrounding environment when the tradition and culture of the place are fully respected without forgetting the technological knowledge that is put at the service of man – builder, creator, architect -, allowing energy insulation, the reduction of heat losses and the reduction of the emission of pollutants into the atmosphere. A “sustainable city”, integrated with good architecture, in a portion of the most uncontaminated territory rich in vibrant popular culture.

We therefore find ourselves in front of 10 units, which are nothing more than reproductions of the large Kanake houses, and which are grouped into 3 distinct sections or villages, as in the real indigenous tradition. The first section, aimed at the exhibition purpose of the project, contains units in which Kanak culture and history are told, with the display of works by Maori, Papuan and Caledonian artists. Offices, auditorium and library meet along the second village section while the third is dedicated to creative activities, such as dance, music, painting and sculpture and also includes a nursery school. In total agreement with the reality of the native people, the units are therefore real “huts”, made with ribs and slats of iroko wood, imported from Ghana, which requires little maintenance and is very resistant to humidity and insects. A pedestrian walk immersed in tropical vegetation connects the 3 villages, highlighting how the apparently archaic “shells” that make up the complex blend perfectly with the columnar pines and the wonderful green spaces present all around.

The wind is captured to ventilate the internal spaces thanks to the millimetrically studied arrangement of the ten huts, partially perforated, contributing to a natural air conditioning situation that allows perfect energy saving. Doors and skylights regulate the explosive flows of air, reproducing the rustling of the trees and reducing the temperature of the external surface by over 50%. Even the very orientation of the convex walls of the buildings, all facing north, allowing the overheating of the surfaces, favors the triggering of air circulation.

All this highlights how timber is not only an aesthetic component but above all represents a functional element: the casing, the load-bearing structure of the building, becomes a closing element aimed at regulating the energy flows linked to the passage of heat, the transmission of light and to protection from solar radiation. A complete synergy between natural elements of the environment itself and cutting-edge technologies.

In addition to wood, materials such as coral and stone, cast aluminum alloy elements, stainless steel, together with concrete and glass were used, capable of guaranteeing heat and light exchanges always in accordance with the aesthetic requirements refined and the complexity of the details.

Another characteristic that is immediately grasped when faced with this architectural work is the feeling of a “construction site still in progress”. An aspect of “unfinished”, which the architect Renzo Piano himself explains thus on the official website of the ADCK (Agence de développement de la culture kanak):

I understood that one of the fundamental characteristics of Kanac architecture is the construction site. “Doing” is as important as “finished”. I therefore thought of developing the idea of a permanent construction site, or rather a place with the appearance of an unfinished construction site.

A building full of meaning in which the poetic and humanistic vision of the work is intrinsic to the use of cutting-edge technologies. Modern materials are used together with traditional materials, giving life to an architecture that can fully exploit the natural resources of the place, respecting its laws and enhancing its beauty.

Always Explain Plan:

(..) the choice of technology is implicit in the choice of building. I find that in an advanced era like ours, in which materials with very high levels of cohesion, with a high degree of workability and tractability are available, it is culturally wrong not to try to shape an architectural language that uses these potentials. It is already mystifying to ask yourself the problem: an architect, a builder, cannot fail to use technological equipment when he creates his design.

And perhaps this is precisely the genius of Renzo Piano, who promoted an architecture with an artisanal character but which keeps alive the search for increasingly technological and high-performance solutions, bending them to the service of the environment in which they operate, of which he himself wants to know its essence, its soul, to be able to tell it in the best possible way through his works.

“Being an architect is a profession of adventure: a frontier profession, balanced between art and science. On the border between invention and memory, suspended between the courage of modernity and the prudence of tradition. The architect does the most beautiful job in the world because on a small planet where everything has already been discovered, designing is still one of the greatest possible adventures.”[1] [1] from Giornale di Bordo, Passigli Editore 2017, page 10